The United States Senate 1789-1833

The United States Senate began as a weak institution with an identity crisis because of its combination of legislative, executive, and judicial powers. The Senate began by meeting in secret with no public galleries and fulfilling a largely revisory role regarding legislation and as an imperfect advisor to the executive. By 1821, it had secured its place as a great deliberative body and an American legislature attractive to the likes of Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster. It did so, in part, by conducting all of its legislative business in public, being responsive to its constituents –both the states and the people—through petitions, resolutions, instructions, and regular correspondence, and acting as an independent and separate institution with regards to executive matters. The Missouri Crises of 1819-1821 marked a moment when the Senate gained its reputation as a great deliberative body with a public presence equal, if not greater, than the House of Representatives.

I want to explore the implications of one of the lessons of the Missouri Crises –namely that slave-states’ interests were not safe in the numerous House of Representatives—and this lesson’s impact on the Senate. Greater growth of the free population in the North compared to the South meant that northern, non-slave states would have a seemingly permanent majority in that body. The admission of the non-slave state of Maine partnered with that of the slave-state of Missouri meant that the principle of equal non-slave/slave state representation in the Senate was articulated in law. The Senate would become a bulwark against the unreliable House and suspect action by the Executive to protect slave-state interests.

By closely examining the Senate’s relationships with the House of Representatives, the Executive, states, and the people as well as the internal workings of the Senate, I will be able to trace the changes in Senate’s status and how it became an integral part of the American state.

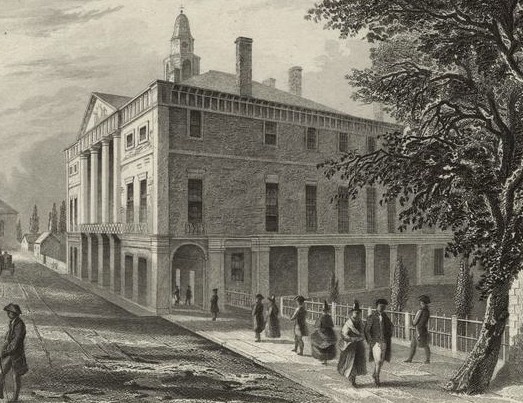

"Old City Hall, Wall St., N.Y." Steel engraving by Robert Hinshelwood, from Washington Irving's Life of George Washington, 5 vol. (1855-59).